skip to main |

skip to sidebar

While I was in the library this week I looked at a column in Cabinet Magazine that outlined a minor history of falling from great heights. It listed a number of people throughout history who have fallen from great heights either intentionally or accidentally. Vesna Vulovic, a Serbian flight attendant, fell from 33,333 feet when her plane was bombed and she survived. Stephen Peer, a tightrope walker, fell while crossing Niagara Falls at midnight. Although there are theories that he was shot by a rival funambulist. Just last year, Father Adelir Antonio di Carli, a Roman Catholic priest from Brazil, took off with 1,000 helium balloons. He floated out to sea and was never seen again. I am really intrigued by these stories, but the one that really blows my mind is Project Excelsior.

On August 16, 1960 Captain Joe Kittenger of the United States Air Force ascended into the stratosphere in a gondola carried by 200ft tall a helium balloon. After 1 hour and 31 minutes Kittenger reached an peak altitude of 102,800 ft. He waited 12 minutes for his balloon to drift over the target landing area and then stepped out of the gondola and began his descent. He fell for 4 minutes and 36 seconds before deploying his parachute and it took him a total of 13 minutes and 45 seconds to finally touch down safely in the New Mexico desert. While falling he reached a top speed of 614 miles while is nine-tenths the speed of sound.

Learning about this completely left me awestruck. I cannot even begin to imagine what that experience must have been like or how he could have taken that step off into space. I am completely enamored with the whole story. What would it have been like to free fall for so long from such a height without even being able to see the ground when you began your descent. To even be able to see the Earth from so far away must have been incredible.

Learning about this completely left me awestruck. I cannot even begin to imagine what that experience must have been like or how he could have taken that step off into space. I am completely enamored with the whole story. What would it have been like to free fall for so long from such a height without even being able to see the ground when you began your descent. To even be able to see the Earth from so far away must have been incredible.

On this jump Kittinger set world records for highest parachute jump, longest parachute free fall and fastest free fall, all of which have yet to be broken. There was a plaque on the front of the gondola that read "This Is The Highest Step In The World"

There was a plaque on the front of the gondola that read "This Is The Highest Step In The World"

Kittinger recovering after the fall

Kittinger recovering after the fall

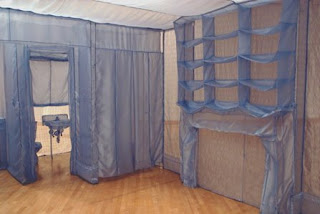

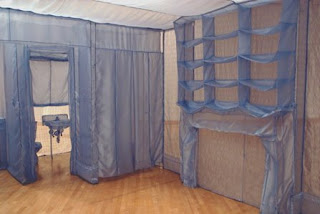

A couple weeks ago I posted a photo by Do Ho Suh, a Korean artist living in the US. I really love his work, so I thought I'd put up some more examples. Do Ho Suh's work is impressive for it's intricacy and delicacy. Having moved from Seoul to New York a lot of his work is inspired by this relocation and the feeling of cultural displacement he has because of it.

Seoul Home/ New York Home/ Baltimore Home/London Home/ Seattle Home is an exact replica of his parents home in Seoul Korea that gains another name as it moves around the country. Being so far from home, he had a longing for a particular space and decided to recreate it and take it with him wherever he went. Suh distinguished between feeling homesick and feeling displaced. When discussing the origination of his idea for the Seoul Home piece Suh said that once he got to New York he couldn't sleep because everything was so loud. He thought back to the last time he had a really good nights sleep and decided that it was when he was at his parent's home in Korea, so he made that home for himself and took it with him when he traveled. That transportability is part of the reason the piece is so delicate and light. He actually carried the home packed in a suitcase with him on the airplane. When making this piece Suh traveled to Korea and measured everything in house down to the location of the holes in the wall. I don't know if any of us have ever paid such intensely close attention to a place where we lived and I think it must have given him a much more in depth understanding of a place that probably existed as an increasing distorted memory before.

Seoul Home/ New York Home/ Baltimore Home/London Home/ Seattle Home is an exact replica of his parents home in Seoul Korea that gains another name as it moves around the country. Being so far from home, he had a longing for a particular space and decided to recreate it and take it with him wherever he went. Suh distinguished between feeling homesick and feeling displaced. When discussing the origination of his idea for the Seoul Home piece Suh said that once he got to New York he couldn't sleep because everything was so loud. He thought back to the last time he had a really good nights sleep and decided that it was when he was at his parent's home in Korea, so he made that home for himself and took it with him when he traveled. That transportability is part of the reason the piece is so delicate and light. He actually carried the home packed in a suitcase with him on the airplane. When making this piece Suh traveled to Korea and measured everything in house down to the location of the holes in the wall. I don't know if any of us have ever paid such intensely close attention to a place where we lived and I think it must have given him a much more in depth understanding of a place that probably existed as an increasing distorted memory before.

348 West 22nd St., Apt A, New York, NY 10011 at Rodin Gallery, Seoul/ Tokyo Opera City Art Gallery/ Serpentine Gallery, London/ Biennale of Sydney/ Seattle Art Muse is a replica of his New York apartment. The title of this piece also accumulates a record of the places it has visited.

348 West 22nd St., Apt A, New York, NY 10011 at Rodin Gallery, Seoul/ Tokyo Opera City Art Gallery/ Serpentine Gallery, London/ Biennale of Sydney/ Seattle Art Muse is a replica of his New York apartment. The title of this piece also accumulates a record of the places it has visited.

A lot of Do Ho Suh's work is also focus on identity and the relationship of the individual to the collective. He utilizes multiples to emphasize the power and strength that come from the collective, sometimes at the expense of the individual. Many small pieces that alone are insignificant are put together to create a whole that overwhelms the viewer. There is a great moment of discovery with many of these pieces when the viewer looks closer and discovers the semi-hidden details.

Floor - A glass floor supported by 180,000 small plastic figures. As individuals they are fragile, but together they can hold a great weight.

Floor - A glass floor supported by 180,000 small plastic figures. As individuals they are fragile, but together they can hold a great weight.

Screen

Screen

Doormat: Welcome (amber)

Doormat: Welcome (amber)

Some/One - Created from thousands of dog tags. Every Korean male must join the army and serve for 2 years. While Do Ho Suh was in the army he said he learned what it was like to be dehumanized.

Some/One - Created from thousands of dog tags. Every Korean male must join the army and serve for 2 years. While Do Ho Suh was in the army he said he learned what it was like to be dehumanized.

There's a pretty good Art:21 on Do Ho Suh that you can watch through the libraries website. The gallery Lehmann Maupin also has a lot of images of his work.

I almost forgot,

In this week's post Beth posted a composite image created by social psychologists. That reminded me of this image contemporary artist Do Ho Suh created by layering all of the yearbook photos in his high school year book with his photo on the top. Beth spoke about how the composite image of a number of different women was overwhelmingly rated as beautiful, and I this that the image resulting from Do Ho Suh’s composite is pretty beautiful and striking as well, but I don’t know if it’s simply because it’s an average of a number of different face. Because it’s black and white Do Ho Suh’s image has an otherworldly almost ghostlike quality. I love the blurred edges around the sides of the face and shoulders that almost look like hair running down his back. It’s really strange how well defined the features all are. I would not have expected that many peoples face to match up so well to make such a clear, well defined face. It makes you realize that there are not as many differences between our features as is usually assumed. Being from Korea, a lot of Do Ho Suh’s work deals with the emphasis in that culture of the importance of the collective over the individual. The individual must give up their personal identity for the good of the whole. One individual person may not be beautiful, but when combined with so many others they become beautiful together.

So I thought that since we are reading something written the journalist Thomas L. Friedman it would be appropriate to show some work by Tom Friedman, the artist. Tom Friedman is an American contemporary artist who works primarily with mundane materials transforming them to create something curious, unexpected or simply astonishing. The majority of his work is almost painfully labor intensive and it really gives you a new sense of the potential of simple ordinary materials.

Self portrait carved from aspirin Signing his name repeatedly with a pen until it ran out of ink

Signing his name repeatedly with a pen until it ran out of ink Pill capsule filled with tiny balls of play dough

Pill capsule filled with tiny balls of play dough 1 lb spaghetti dried and attached end to end in a loop

1 lb spaghetti dried and attached end to end in a loop 1 continuously shaved pencil

1 continuously shaved pencil toothpicks

toothpicks

Learning about this completely left me awestruck. I cannot even begin to imagine what that experience must have been like or how he could have taken that step off into space. I am completely enamored with the whole story. What would it have been like to free fall for so long from such a height without even being able to see the ground when you began your descent. To even be able to see the Earth from so far away must have been incredible.

Learning about this completely left me awestruck. I cannot even begin to imagine what that experience must have been like or how he could have taken that step off into space. I am completely enamored with the whole story. What would it have been like to free fall for so long from such a height without even being able to see the ground when you began your descent. To even be able to see the Earth from so far away must have been incredible.  There was a plaque on the front of the gondola that read "This Is The Highest Step In The World"

There was a plaque on the front of the gondola that read "This Is The Highest Step In The World"

Kittinger recovering after the fall

Kittinger recovering after the fall